Catholic fact check: Father Edward Schillebeeckx and Implicit Conclusions

National Catholic Reporter, Volume 1, Number 3, 11 November 1964

National Catholic Reporter, Volume 1, Number 3, 11 November 1964The following quotation (or variations thereof) is attributed to the controversial theologian Father Edward Schillebeeckx, O.P.:

“We express it diplomatically [now], but after the Council we will draw the implicit conclusions.”

The citation given for the quote is almost always the same:

De Bazuin, No. 16, 1965

Says who?

The quote has circulated for years now. Perhaps most famously, it was used in the book Iota Unum, by Romano Amerio1, and in Archbishop Lefebvre’s Open Letter to Confused Catholics2.

From Lefebvre:

Fr. Schillebeeckx admitted it. “We have used ambiguous terms during the Council and we know how we shall interpret them afterwards”. Those people knew what they were doing.

Update: 04/22/2021

The theology podcast, Reason and Theology, recently aired an episode on this very quotation. The host, Michael Lofton, and his guest, Riverrun, discussed both the quotation’s context, and its implications. Most thrillingly (for me, usually reliant on Google Translate), Riverrun will be providing a recently-completed full translation of Fr. Schillebeeckx’s article.

See the translation by Gregory Arblaster here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1aqttHiQPqQmQ5DxAXuaQ6GtUuVWS_kmJ/view

See the podcast’s bibliography here: https://reasonandtheology.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Bibliography-for-Schillebeeckx-and-Accusations-of-_Weaponized-Ambiguity_-at-Vatican-II-with-Riverrun.pdf

See the podcast “Schillebeeckx and Accusations of “Weaponized Ambiguity” at Vatican II with Riverrun” here: https://reasonandtheology.com/2021/04/21/schillebeeckx-and-accusations-of-weaponized-ambiguity-at-vatican-ii-with-riverrun/

Did he say it?

Given the complexity of this particular saga, I will jump to the conclusion.

Schillebeeckx did not say it; he quoted someone else who said it, and he disagreed with the speaker.

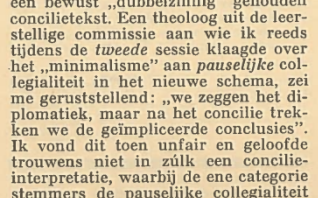

In the article, “Wij denken gepassioneerd en in cliche’s” (“We speak passionately and in cliches”), published in Dutch Catholic weekly magazine De Bazuin, volume 48, number 16 (Jan. 23rd, 1965), pp. 4-6, Schillebeeckx said3:

Een theoloog uit de leerstellige commissie aan wie ik reeds tijdens de tweede sessie klaagde over het “minimalisme” aan pauselijke collegialiteit in het nieuwe schema, zei me geruststellend: “we zeggen het diplomatiek, maar na het concilie trekken we de geïmpliceerde conclusies”. Ik vond dit toen unfair en geloofde trouwens niet in zulk een concilieinterpretatie, waarbij de ene categorie stemmers de pauselijke collegialiteit zou negeren en de andere categorie ze zou impliceren! Er had ofwel een duidelijke tekst moeten zijn waarin het maximalisme (wat de collegialiteit bewat treft) ondubbelzinnig werd geformuleerd, ofwel een duidelijke tekst waarin de eerder minimalistische opvatting (die het schema uitdrukkelijk formuleert) wordt ontdaan van haar dubbelzinnige vaagheid-door-verzwijging van het eigenlijke probleem.

A theologian from the doctrinal commission to whom I’d already complained in the second session about the ‘minimalism’ of papal collegiality in the new schema, attempted to comfort me by saying, “We say it diplomatically, but after the council, we will draw out an implied conclusion.” At the time, I found this unfair, and besides, I do not believe in such an interpretation of the council whereby one category of voters ignore papal collegiality and the other category implies it! There should have been either a clear text, wherein maximalism (regarding collegiality) was unambiguously formulated, or a clear text wherein a more minimalistic interpretation (which the schema explicitly formulates) is gutted of its ambiguous vagueness-through-silence of the actual problem. (Translation by Gregory Arblaster; emphasis added)

(Oddly, one website4 got the attribution right.)

While it would be correct to say that Schillebeeckx was aware of the tactic of manipulating ambiguous conciliar documents, he disagreed with the practice. Schillebeeckx may be justly accused of many conciliar and theological crimes, but surprisingly, not this one.

How I found the correct citations is below, as is the full, complicated context of Schillebeeckx’ quotation.

Unexpected success

Adding Bazuin to my Schillebeeckx terms (ignoring volume and year terms for now) led me to a collected bibliography of Schillebeeckx’s works5 - a perfect find!

I scanned the document for all references to articles in De Bazuin - of which there were a significant number. On page 44, we find the following citation:

Wij denken gepassioneerd en in cliché’s, in: De Bazuin 48 nr. 16 (Jan. 23rd, 1965), 4-6.

This is quite promising. Confusing volume, issue, and number information is common, so I’m not surprised that at some point the volume number got lost.

Now all I need to do is find the right De Bazuin, find out who holds it, if they hold the right issue, and if they accept requests from independent researchers.

Finding the right magazine

In Worldcat, there are at least a dozen “De Bazuin” journals and magazines, with varying subtitles.

An Ecclesia Dei article6 says that De Bazuin was run by Dutch Dominicans from 1911-2002. A FishEaters forum post7 calls it the “magazine of the Dutch Ecclesial Province.” A New York Times article8 calls it a “progressive weekly”. The Catholic News Service called it a “Dutch Catholic weekly,”9 and that it was a national paper run by Dominicans.10

Distilling from the above sources and a few more newspapers, I can name at least several editors-in-chief: Fr. Nicol Versluis, Fr. Thomas Jannsens, Fr. H. van Gelder11, O. S. A., and curiously in 1967, Dr. J. Colijn - a Protestant.

One of the less glamorous aspects of researching esoteric modern Catholic records is the multiplicity of records. It’s not uncommon for the same book, journal, or magazine, etc. to have multiple records in Worldcat. I also am unsure what this item might be classified as - a periodical? A magazine? A journal? If it was collected and rebound, maybe even a book?

The only way forward is the honest one: a title search in Worldcat for Bazuin (taking no chances, no De’s), sorting alphabetically by title, and scouring each listing. What I am hoping for is any term connected to (the Dutch words for) Catholic, Dominicans, 1911-2002, or any of the editors.

Several hours of Dutch digging netted this promising record: a De Bazuin12 published from 1912-2002 by Dominicans. The “Notes” section of that record is particularly helpful, if you’ll pardon the Google Translate:

“From about 1925 with subtitle: popular religious-scientific and apologetic weekly for the Netherlands and colonies; from 1947? with subtitle: weekly magazine for the proclamation of faith; later with subtitle: opinion weekly for church and society; then: newsmagazine for faith and society, culture and spirituality.”

Requesting the right issue

Worldcat says that 16 institutions hold that De Bazuin. In a normal situation, you should request interlibrary loans through your public library (or university library - whatever your library affiliation is). My local library’s ILL services are indefinitely suspended, so I am operating as an independent researcher fully at the mercy of these institutions.

I went through the 16 libraries that should have De Bazuin, and searched their library catalogs so that I could see the listing information (i.e. - do you have the issue I need?). This catalog record13 is a good example of what a serial listing looks like in a catalog record.

Eventually, I flagged about a dozen institutions that I thought might have the right issue. Then I had the bonus task of finding their “Contact” form - no small feat these days. In my email, I asked three separate things: 1) Did their library have the correct De Bazuin, 2) Did they have the relevant issue, and 3) Did they lend items to independent researchers?

I heard back from the majority of institutions within 12 hours - remarkable! I got a variety of answers: no, we have a different Bazuin; we have the magazine but not that issue; actually we got rid of a lot of our print holdings (and Worldcat doesn’t automatically update information like this); we have it but no one is on site; we have it but you’d need to request it through a library (more than fair); we don’t have it but here’s more information about Schillebeeckx that may help; and we don’t have it but here are a few places that may (very kind!).

And then, the most unexpected: one library simply said ‘see attached’. There was the article in full!

A quick skim of the article made it clear that the article was a response, or follow-up, to an earlier article by Schillebeeckx. I checked the bibliography I’d found earlier, got the citation (December 23, 1964 - about a month before the article I had), and once again fell upon the generosity of this Dutch library. They obliged immediately, and I now had 2 full-text articles to sift through.

Some stabs in the dark with Dutch terms about “conclusions” and “implicit” got me to the quote under review.

Skimming the two articles also sparked a number of questions.

The tone seemed apocalyptic: Schillebeeckx spoke of something at the Council that “carries the possibility of an at least inner schism in the minds of the faithful” (December 1964: “die de mogelijkheid in zich draagt van een althans innerlijk schisma in de geesten der gelovigen,”), and that felt like the “sadness when the dead loved one’s body is still in the side room” (also December: “Het is steeds moeilijk iemand in droefheid te troosten als het lijk van de dierbare afgestorvene nog in de zijkamer ligt”).14

What happened?

In this instance, I will save you the tedium of research reconstruction, as the tedium of the topic will be penalty enough.

November 1964 saw the closing of the third session of the Second Vatican Council, what was infamously called “Black Week,” and uproar over the definition of collegiality.

In a radical act of self-care, I refuse to summarize the substance of the collegiality fight. Robert de Mattei15 and Father Ralph Wiltgen16 cover these events thoroughly. Commonweal Magazine has a good summary17.

Confining myself to the actions:

The Council Fathers were about to vote on Lumen Gentium (LG), which had a chapter on collegiality. The ambiguity of this chapter had caused numerous fights between ‘conservatives’ worried about weakening the Pope’s authority, and ‘progressives’ who sought a more flexible definition of an outdated papalism. At the last minute, Pope St. Paul VI appended an “explanatory note” to LG. Archbishop Pericle Felici read the note at the Council without warning and without any time for debate. It was unclear at the time if Pope Paul had the authority to “intervene”, what the note really meant, and what authority it had in relation to LG. LG was passed by an overwhelming majority, and the session closed shortly thereafter.

The fallout

Almost immediately after Pope Paul’s note, rumors began to circulate. Newspapers seized on a melodrama involving not only conservatives versus progressives, but the no less important struggle between the Roman Curia and the rest of the bishops.

Newspapers picked up the story almost immediately:

“Collegiality teaching accepted, but in a watered-down form”. “Collegialiteitsleer aanvaard, maar in afgezwakte vorm Meerderheid voor drie hoofdstukken van Kerkschema”. “De Tijd De Maasbode”. Amsterdam, 1964/11/18, p. 6. http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:011233728:mpeg21:p006

Schillebeeckx wrote an article for De Bazuin (“De waarheid over de laatste concilieweek,” or “the truth about the last council week,” De Bazuin 48 nr. 12 (Dec. 23th 1964), 4-6) to clear the air.14

Header from: Schillebeeckx, Father Edward. “De Waarheid over De Laatste Concilieweek.” De Bazuin 48, no. 12 (1965): 4-6.

Rather than clear the air, it provoked a firestorm among readers, prompting a response from Schillebeeckx a month later (“Wij denken gepassioneerd en in cliché’s,” or “We speak passionately and in cliches,” De Bazuin 48 nr. 16 (Jan. 23rd, 1965), 4-6).3

Header from: Schillebeeckx, Father Edward. “Wij Denken Gepassioneerd En in Cliche’s.” De Bazuin 48, no. 16 (1965): 4-6.

In broad strokes, Schillebeeckx defended the legality of Pope Paul’s actions, but considered his actions imprudent considering the already suspicious atmosphere. He airs some complaints that the minority (generally conservatives - he mentions Lefebvre by name) were treated better than progressives. He accuses newspapers of fanning the flames.

In his own words from the December 1964 article14:

Het enige verschil tussen de tekst zelf van de constitutie en de ,,verklarende nota” ligt hierin, dat de onbeslistheid van de conciliaire tekst veeleer in de richting van een reëel onderscheid tussen deze twee titels wordt verbogen…De constitutie op zich laat de openheid, om deze laatste visie een kans te geven. Door de ,,verklarende nota" wordt elke gedachte aan de bevordering van deze kans weggenomen, hoewel ondanks alles niet positief uitgesloten, want men zegt niet, hoe men dit ,,afzonderlijk" optreden van de Paus moet begrijpen.

The only difference between the text itself of the Constitution and the “Explanatory Note” lies in the fact that the indecision of the Conciliar text is rather bent towards a real distinction between these two titles…The constitution itself leaves the openness to give this last vision a chance. The “explanatory note” removes any thought of promoting this opportunity, although not positively excluded despite everything, because it is not said how to understand this “separate” action of the Pope. (Google Translate)

The “two titles” are “the Pope as Chief Pastor of the whole Church" and “the Pope as Head of the College.” The former was the “maximalist” title; the latter was the “minimalist” title.

Schillebeeckx clarifies in January 19653:

De vage openheid die het schema zelf opzettelijk had gelaten, werd door die nota blootgelegd. Bij herlezing van de twee teksten wordt het steeds evidenter: de nota onderlijnt datgene wat de Constitutie zelf zegt, maar dan zonder de diplomatieke vaagheid waarin de tekst was gehuld…De minderheid was niet tegen de collegialiteit zoals de tekst die letterlijk formuleerde, maar wel tegen het hoopvolle perspectief dat de meerderheid van de leerstellige commissie bewust vaag en wat al te diplomatiek erin wilde laten meeklinken, zonder het in de tekst le formuleren.

The vague openness intentionally left by the schema itself, was exposed by that note. At the rereading of the two texts, it becomes even more evident; the note underscores what the constitution itself says, but without the diplomatic vagueness in which the text was shrouded…The minority was not opposed to collegiality as was literally formulated in the text, but was against the hopeful perspective that the majority of the doctrinal commission wanted to resonate with using conscious vagueness, and all too diplomatic language, without formulating it as such in the text. (Translation by Gregory Arblaster)

One last, unintentionally hilarious quotation from Schillebeeckx in January3:

Ik vind het zelf indroevig, dat ik twee artikelen moet schrijven met allerlei theologische distincties en uitleg om enigszins klaarheid te hrengen. Als zo iets nodig is, wijst dit duidelijk op een ondoorzichtige situatie. En de gelovigen zijn al deze geleerde uitleg grondig beu. Ik kan daarmee slechts instemmen. Ook hij paus Johannes moesten we voortdurend distincties maken. Maar zijn houding was menselijk overrompelend en bevrijdend, en daarom maakten we geen spektakel als hij dwars tegen het concilie in “St.-Jozef” prompt in de canon plaatste, ook al had de Kerk daar kennelijk geen uitgesproken behoefte aan. Johannes had met dezelfde nonchalance Maria tot Moeder van de Kerk kunnen proclameren. Goedmoedig zouden we geglimlacht hebben.

I myself find it depressing that I have to write two articles with all kinds of theological distinctions and explanations in order to bring some clarity. When such a thing is necessary, it clearly indicates an opaque situation and the faithful are thoroughly fed up with all these learned explanations. I can only agree with that. We also had to constantly make distinctions with Pope John, but his attitude was overwhelmingly humane and liberating which is why we did not make a spectacle when he suddenly placed St. Joseph in the canon at odds with the council, even though the church had no express need for it. John could have proclaimed Mary as Mother of the Church with the same nonchalance. We would have kindly smiled on. (Translation by Gregory Arblaster)

Desipte its minimal long-term effects, the event clearly stayed with Schillebeeckx, as he brought it up years later in interviews.18

Conclusion

In a sense, it didn’t matter what Pope Paul’s note said, or what Lumen Gentium said. It mattered what people thought they said.

Some saw Pope Paul’s note as a desperately needed corrective against the dangerous ambiguity of Lumen Gentium. (Pope Paul did not make any edits to Lumen Gentium.)

Some saw this as a victory of Pope Paul, the Curia, and papal maximalism/papalism/papal monarchism. (The authority of the letter in relation to Lumen Gentium was totally unclear, and was notable only to the few people following the issue.)

Some saw this as a watering-down of the Council’s intended definition of collegiality. (I will pay $50 to anyone who can give me a definition of collegiality, right now.)

Some factions (such as Schillebeeckx) saw this as proof positive that relying on future manipulation of textual ambiguity to get one’s way was doomed. (I need no examples to show how wrong he was.)

Some factions believed Pope Paul had violated Council procedures and the rights’ of the bishops for the sake of a misguided minority. (He did not violate procedures or rights, nor would conservatives now consider Pope Paul as “one of them”. This goes to show how messy history is in the moment!)

The ‘progressives’ saw Pope Paul as too generous to the ‘conservatives’, and saw themselves as ambushed and ignored at turns. All their hard work had gone up in smoke! The ‘conservatives’, momentarily allied with Pope Paul, saw a moment of hope in the fight against modern machinations.

For our purposes, the two takeaways are:

Fr. Schillebeeckx was opposed to intentional ambiguity. He wished that the council documents would say exactly what they meant, and he did not think a future of ambiguity was tenable.

This was a fight about perception, rather than content, and fueled by hungry newspapers and hysterical theologians. To this day, debate continues about what collegiality is, what Lumen Gentium means, and what Pope Paul’s note means.

Given that collegiality still requires pages of explanations in dissertations (such as here19 or here20 or here21), I am not convinced anyone at the Council or even now fully understands what the texts themselves actually mean.

I defer to James Hitchcock22 for a closing summary:

Such was the euphoria of the conciliar years that it was scarcely possible at the time to understand the immense importance of the public relations triumphs which accompanied it. It is probable, for example, that in 1960 most Catholics had scarcely heard of the Roman Curia; still less did they regard it as a chief obstacle to progress in the Church, even in the unlikelihood that they considered such progress desirable.The media deliberately made famous such men as Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani solely in order to establish him as the principal villain in a drama. They “educated” people on abstruse issues like collegiality solely in order to enlist their sympathies on one side of the struggle. Every discussion was cast relentlessly in terms of a conflict between “progressives” and “reactionaries.” Every vote was assessed as either a victory or a defeat for the respective forces of light and darkness. The immense subtleties of the questions at stake, and above all the call to spiritual renewal which was the Council’s chief exhortation to Catholics, did not lend themselves to effective media presentation and were passed over as irrelevant.

Sources

Amerio, Romano. Iota Unum : A Study of Changes in the Catholic Church in the Xxth Century. Kansas City: Sarto House, 2004. ↩︎

Lefebvre, Archbishop Marcel. An Open Letter to Confused Catholics. [Manila]: Society of St. Pius, 1986. ↩︎

Schillebeeckx, Father Edward. “Wij Denken Gepassioneerd En in Cliche’s.” De Bazuin 48, no. 16 (1965): 4-6. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Fr. Pierre-Marie, O.P. “Little Catechism of the Second Vatican Council (Part Two).” Le Sel de la terre 93 (2015). http://www.dominicansavrille.us/little-catechism-of-the-second-vatican-council-part-two/. ↩︎

Schoof, Ted, and Jan van de Westelaken. “Bibliography 1936-1996 of Edward Schillebeeckx O.P. .” https://schillebeeckx.nl/wp-content/uploads/2008/11/Bibliografie-Sx-nwe-versie.pdf. ↩︎

“Fruits of Vatican Ii: Ii: Process Analysis Concerning the Religious Memberships - Renewal in Unity with and in Accordance to the Doctrine or False Interpretations?”, https://www.ecclesiadei.nl/docs/fruits-of-vatican_ii-part_2.html. ↩︎

“Timebombs in Vatican Ii - Quote Needed.” Updated April 6, 2006, https://www.fisheaters.com/forums/showthread.php?tid=5439. ↩︎

“Jazz Vs. Gregorian Mode at Mass Reflects Dutch Catholic Rift with Vatican.” New York Times, February 8 1976. https://www.nytimes.com/1976/02/08/archives/jazz-vs-gregorian-mode-at-mass-reflects-dutch-catholic-rift-with.html. ↩︎

“Situation of Church in U,S. ‘Alarming’: Schillebeeckx “. Catholic News Service, January 20 1968. https://thecatholicnewsarchive.org/?a=d&d=cns19680120-01.1.13. ↩︎

“Dutch Jesuit Weekly May Have to Close “. Catholic News Service, September 17 1962. https://thecatholicnewsarchive.org/?a=d&d=cns19620917-01.1.29&srpos=3. ↩︎

“Minister Co-Editor of Catholic Magazine.” Catholic News Service, September 27 1967. https://thecatholicnewsarchive.org/?a=d&d=cns19670927-01.1.29&srpos=11. ↩︎

Ordo Fratrum, Praedicatorum, and Bazuin Stichting De. “De Bazuin : Weekblad Voor Katholieken En Zoekenden Naar De Waarheid.” [In Dutch]. De bazuin : weekblad voor katholieken en zoekenden naar de waarheid. (1912). ↩︎

“Catalog Record for De Bazuin : Weekblad Voor Katholieken En Zoekenden Naar De Waarheid.” International Institute of Social History (Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis). https://search.iisg.amsterdam/Record/1364732. ↩︎

Schillebeeckx, Father Edward. “De Waarheid over De Laatste Concilieweek.” De Bazuin 48, no. 12 (1965): 4-6. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

De Mattei, Roberto, Patrick T. Brannan, and Michael J. Miller. “The Second Vatican Council : An Unwritten Story.” [In English]. (2013). ↩︎

Wiltgen, Ralph M. The Rhine Flows into the Tiber : A History of Vatican Ii. Rockford, Ill.: Tan Books, 1985. ↩︎

Wilkins, John. “Bishops or Branch Managers? Collegiality after the Council.” Commonweal Magazine, October 1, 2012. https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/bishops-or-branch-managers. ↩︎

Prendergast, Michael R., and M. D. Ridge. Voices from the Council. Portland, Or.: Pastoral Press, 2004. ↩︎

Parry, Enrico Valintino. “A Critical Examination of Collegiality in the Southern African Catholic Bishops’ Conference (Sacbc) : Towards a Local Model of Collegiality.” 2005. http://worldcat.org. ↩︎

Caldwell, Paul Raymond. “Yves Congar, O.P.: Ecumenist of the Twentieth Century.” Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Marquette University, 2012. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/223 (223). ↩︎

Blanchard, Shaun London “Eighteenth-Century Forerunners of Vatican Ii: Early Modern Catholic Reform and the Synod of Pistoia.” Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Marquette University, 2018. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/774 (774). ↩︎

Hitchcock, James. Catholicism and Modernity : Confrontation or Capitulation? Ann Arbor, Mich.: Servant Books, 1979. ↩︎