Are childfree weddings traditional?

“Penny wedding,” David Wilkie (1818)

“Penny wedding,” David Wilkie (1818)One of the most hotly debated issues in planning a wedding is whether or not to invite children. Some people feel that having children at a wedding can be an intrusion or a distraction for guests intent on participating in and honoring a very grown-up ritual. Others can’t imagine a wedding celebration without children. One undeniable factor is the additional financial burden inviting a number of kids can incur. - Emily Post’s Wedding Etiquette, 2001

For fun, let’s explore the claim that it is traditional to have children at Catholic weddings.

Defining terms

By “children,” I mean small people who are roughly between the ages of “eating solids” and “teenagers.”

And by “weddings,” I primarily mean “wedding receptions.” While I do mention children at Mass (she said demurely, nudging the hornet’s nest a bit more), I am most interested in the reception.

Weddings are dictated far more by custom and etiquette than by liturgical and canonical strictures. They are extremely variable events, it’s rare that anyone thinks to write anything down, and there are frequent divergences between what was written down and what actually happened.

So to keep this study useful, I will limit myself to roughly the last 150 years in America. Pre-industrial society had a different approach to weddings, and very generally speaking, nuptial events were more likely to place in the home.

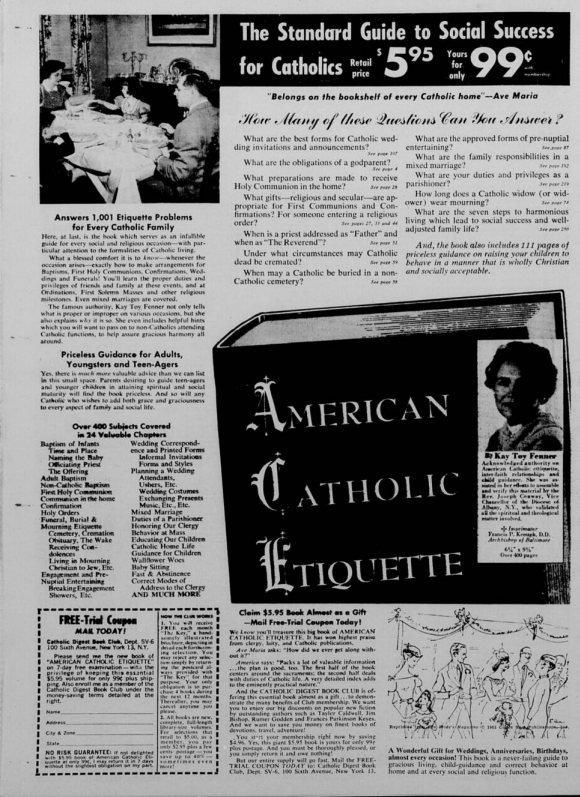

American Catholic Etiquette (1961-1965)

Kay Toy Fenner wrote her encyclopedic work American Catholic Etiquette in 1961, with subsequent editions through 1965. Her book bore an imprimatur from Francis Patrick Keough, Archbishop of Baltimore. Here1 is one review published in the Catholic Transcript, shortly after the book was published.

Here is what Fenner said:

Children old enough to behave properly in church may be brought to the church ceremony because, theoretically, a Catholic church service is always open to all. But one should not expect to bring children to a wedding reception (and one should never ask permission to bring them) if their names were not written on the inner envelope of the invitation in which one has received. Even when they are so included, it is better not to bring children under fourteen to the nuptial entertaining. A reception or breakfast is entertaining planned for adults. The best-behaved children are apt to become bored and restless at such a party. If they are allowed to run about and annoy guests, they can ruin the occasion. Parents should not expect to take children with them to wedding entertaining and should not express surprise or injury if their children are not invited. (page 175)

To a wedding breakfast as just described, children under fourteen would not be invited, and frequently children under sixteen would not. Parents should not expect young children to be invited to such a party and of course should never bring them unless they have been specifically named in the invitation. (page 211)

To the three types of entertaining just described, children are seldom invited. Perhaps it should be pointed out that a bride may, if she wishes, invite the family children to any style of wedding entertaining, but she is never under any obligation to do so. When and if children of any age are invited to a wedding reception, parents should make it their primary obligation to see to it that their offspring behave properly and quietly and do not detract from the enjoyment of other guests. (page 214)

Verdict: well-behaved children at the ceremony, no children under 14 at the reception

Emily Post’s Etiquette (1922)

Ah, say the naysayers, but that was the 1960’s. Can anything good come from that time? Where are our reliable pre-55 wedding customs? Let us look further afield.

Emily Post needs no introduction. Post’s first blue book of Etiquette was published in 1922, and has no specific section for children at weddings. Indeed, there is no mention of children at all at weddings. In Chapter 21, she does mention separate invitations for the church ceremony and the reception. In Chapter 22, the presumption is that the ceremony is at the church, and the reception is at home. One may be inclined to think a domestic reception would favor children, but the reception she described is quite formal, which would suggest no children.

In 1940, Post wrote a book called Children are People, which details expected behavior from children, and from adults to children. Children at weddings are mentioned nowhere in her detailed exposition.

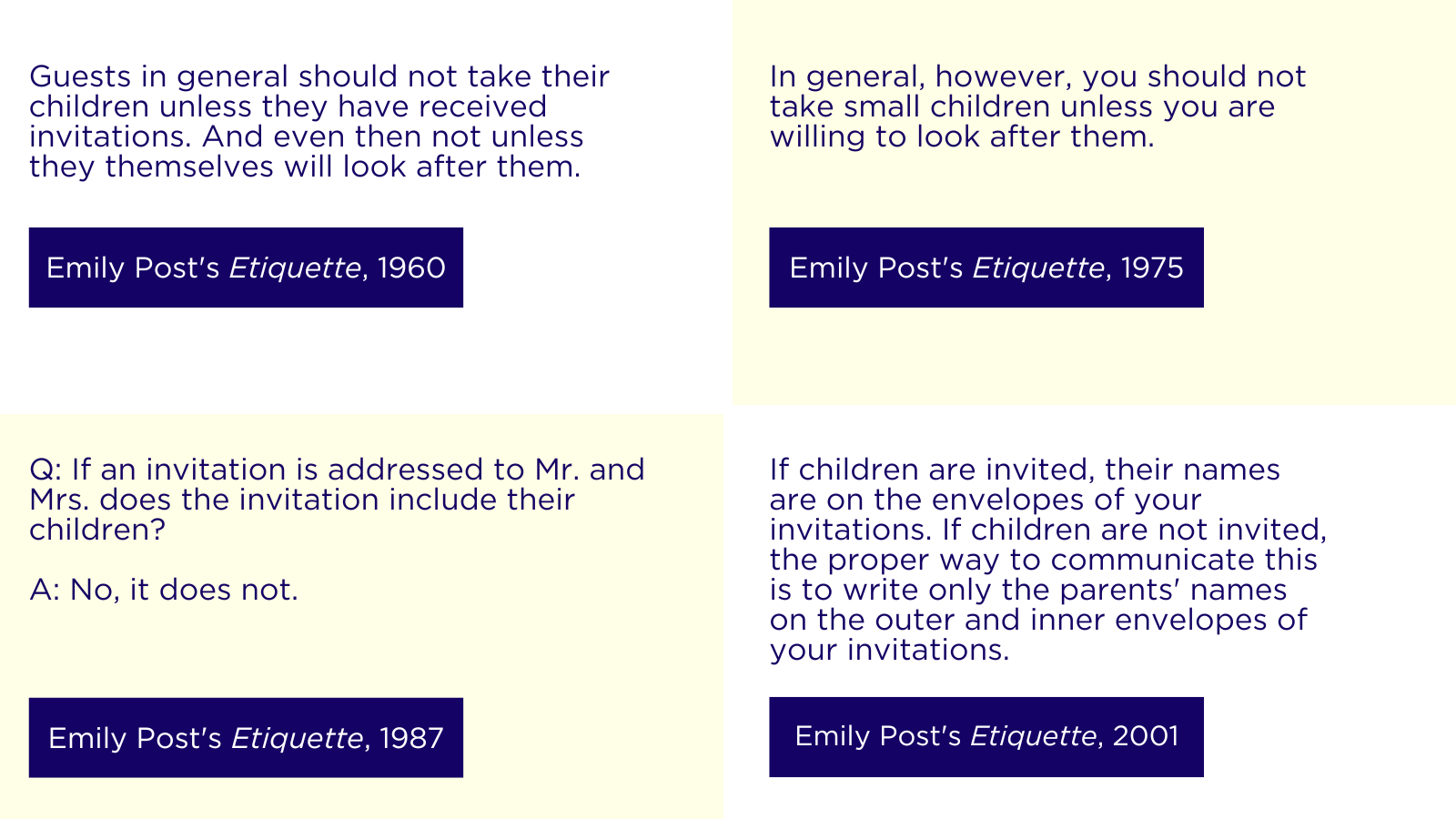

In later editions of Post’s Etiquette, children at weddings were still barely mentioned. The 1997 edition finally sees the first acknowledgement of the issue, allowing it to be hotly debated. The next generation of Postians outline how to approach children at weddings, but it is clear that the default wedding reception has no children.

Verdict: children are only invited if their names are on the invitation

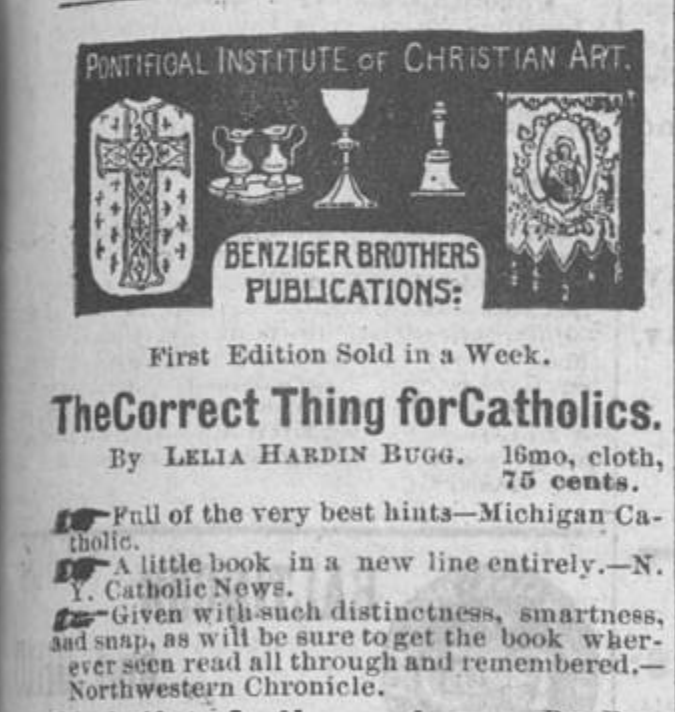

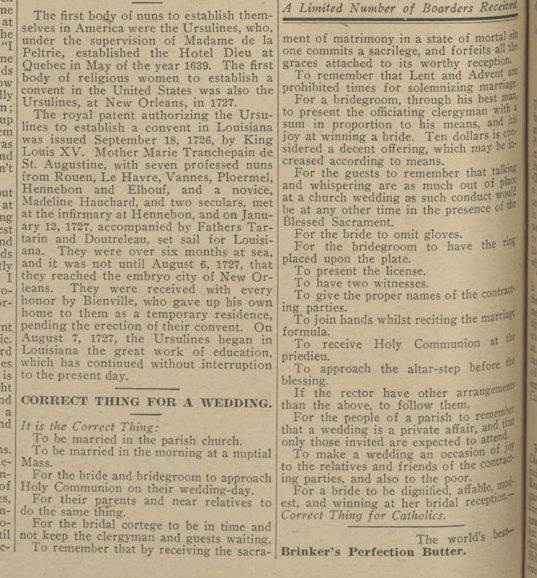

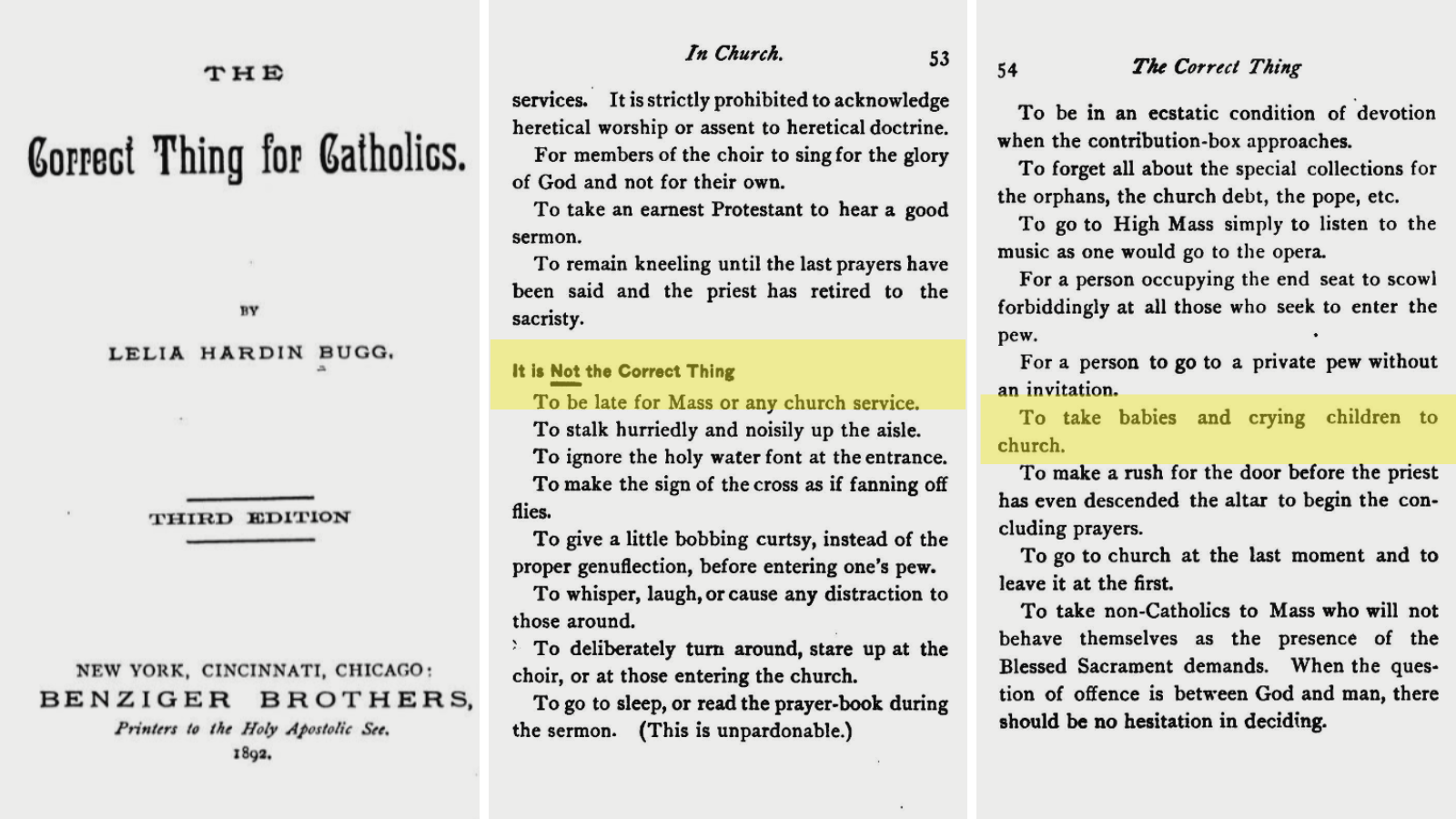

The Correct Thing for Catholics (1892)

The crowd grows restless. The cry goes round the battlements: Emily Post is not Catholic! Your sources are inapplicable!

The point is well taken. As recompense, I offer Lelia Hardin Bugg’s wildly popular The Correct Thing for Catholics, published in 1891 and on its twelfth edition by 1892. The authoress’ deserving biography remains to be written, but one curious fact is that she “was placed in the care of Right Reverend Bishop Hennessy.”2

Excerpts of her book were printed in the Catholic Telegraph in the 1900s and 1910s.

As with many good things, she would be forgotten then later rediscovered in the mid to late twentieth century.3

Buggs does not mention children at weddings, but she makes no bones about children at Mass: a resounding no! It is highly unlikely Buggs would so definitively recommend no children at Mass, but recommend children at weddings.

She said:

“It is the correct thing…To be married in the morning at a nuptial Mass.” “It is not the correct thing…To forget that the late council of Baltimore prohibited the celebration of weddings in church after five o’clock in the evening.” “It is not the correct thing…To take babies and crying children to church.”

Verdict: inferred no children

Conclusion

Two other works of Catholic etiquette, Catholic laymen’s guide to etiquette (1957) and The polite pupil (1915), make no mention of children at weddings.

So these five sources, ranging from the late nineteenth century through the 1960s, all very popular, all reprinted several times, at least one with an imprimatur, say either:

- Don’t bring children to Catholic wedding receptions.

- Don’t bring children to Mass.

- Nothing on the subject of children at weddings. (To my mind, if an etiquette book is silent on a custom, that is evidence the custom was not common. One could argue the opposite: the custom was so common that no one thought to write it down.)

There is broad consensus that one should never assume that children are invited, unless the invitation includes the names of the children, or says “and family.” In the same breath, brides are admonished not to add “no children” on the invitation, because it is unnecessary (if you know etiquette) and it sounds cold.

What to make of all of this? The easy answer - that the world went insane in the mid-twentieth century - gives us no solace, because etiquette discouraging children at receptions (even Mass!) can be traced back much earlier. This reluctance to include children may seem deeply strange to traditionalists today.

Here are two ideas which may help potentially explain this odd tradition.

The shift of wedding receptions from a domestic occasion to a formal event. It used to be much more common for weddings to take place at home. In some liturgical books, the rite of blessing the bedchamber (benedictio thalami) immediately followed the nuptial ceremonies. This suggests that the priest was in or near the married couple’s home already, celebrating the wedding. After the Industrial Revolution, weddings went through amazingly rapid developments. Advertisements, especially the rise of visual and not just text advertisements, fueled wedding receptions as a formal, highly material event. A wedding and a meal at home would likely have children. A wedding at church and a formal brunch or dinner at a club would be less likely to have children.

The time of day for weddings. Wedding breakfasts4 used to be more common, because weddings themselves used to happen earlier in the day (and not always on Saturdays!). The Council of Baltimore condemned afternoon and evening weddings (one reason why is poignantly illustrated in this 1918 short story5). Time of day makes a big difference both in the formality of the event, and the ease of involving children.

All of that said, it would be naive to write on this topic without acknowledging the rife antinatalism these days. The disdain (or even hostility) toward babies and children can be felt everywhere. While adults-only ceremonies have historical precedent and can be wonderful, it’s no wonder that our current culture makes us traditional Catholics push back and invite children.

Some would argue that the rife antinatalism, which can be felt everywhere now, urgently outweighs some old, materialistic etiquette books. Bring on the children and let it be a witness!

Some others, perhaps some parents, would argue that one can be pro-family without bringing children to every occasion. Leaving the children at home may be more pleasant for everyone involved, children included.

For a final verdict? Etiquette will tell the guests not to assume that their children are included. There’s precedent for both childfree and child-filled receptions; it’s up to the couple, and the type of reception that they want.

Sources

“Balancing the books,” The Catholic Transcript, Volume LXIV, Number 31, 30 November 1961. https://thecatholicnewsarchive.org/?a=d&d=CTR19611130-01.2.44&srpos=1 ↩︎

Immortelles of Catholic Columbian Literature: Compiled from the Work of American Catholic Women Writers. United States: D. H. McBride, 1897. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Immortelles_of_Catholic_Columbian_Litera/HSATAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=lelia ↩︎

“Cry Pax! A Column Without Rules,” National Catholic Reporter, Volume 2, Number 18, 2 March 1966. https://thecatholicnewsarchive.org/?a=d&d=ncr19660302-01.2.2&srpos=39 ↩︎

“How To Plan The Perfect Wedding Breakfast,” Bredenbury Court Barns, 05/21/2022. https://www.bredenburycourt.co.uk/wedding-breakfast/ ↩︎

C. D. McEnniry, CSsR. “Father Tim Casey: An Evening Wedding Frustrated,” Our Sunday Visitor, 31 March 1918. https://thecatholicnewsarchive.org/?a=d&d=OSV19180331-01.2.13&srpos=12 ↩︎